David Rose

Active member

Last summer, Andy Chapman re-published many of the writings of the late Mike Boon. One of the highlights of his compilation volume, issued under the title A Spider?s Thread of Shining Silver, was Boon?s account of The Great San Agustin Rescue ? the 1980 retrieval by an international team of the badly injured Pole, Josef Huber, from a depth of ? 600 metres in the Sotano de San Agustin, part of the Huautla system in Mexico.

Last week, Andy Eavis, Tim Allen, Pete Ward and I shared a forest camp in the nearby Sierra Negra with some of the heroes of this story and went caving with them. Etienne Degrave, the doctor who tended Huber underground for days, Richard Grebeude and Jean-Claude ?Jack? London may be rather older now, but they have lost none of their enthusiasm for underground adventure. Thanks to the many books and articles about it and the hard-charging personality of its leading light, Bill Stone, the Huautla project is more famous, and a little deeper. But Degrave, Grebeude and their friends from the Group Speleo Alpin Belge (GSAB) have quietly been knocking off extraordinary achievements 30km away from Huautla for many years. Their finds include one cave more than 1,300 metres deep, a total of six deeper than 1,000 meters and several systems more than 20 km long ? all managed on just a tiny fraction of the corporate sponsorship amassed by Stone?s group and its attendant media hoopla.

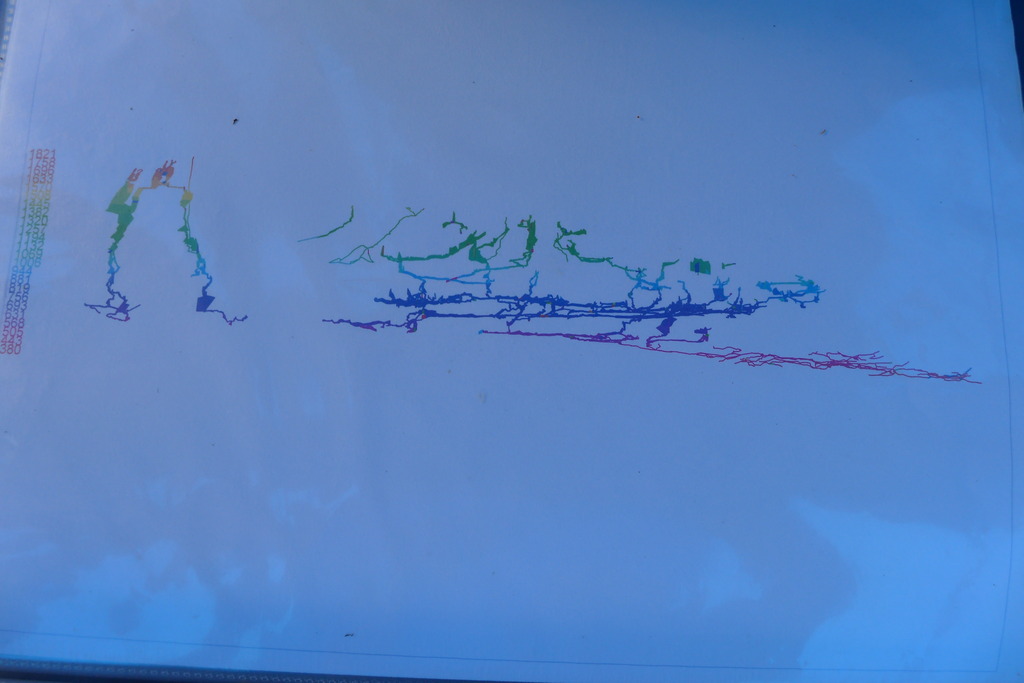

We were in Mexico for a specific purpose: as part of the Eavis ? Allen giant cavern laser scanning project, we wanted to make a 3D scan of the main chamber of La Muneca, discovered by GSAB at a depth of -450 m in 1999 and not visited since.

It took a while to reach basecamp: a flight to Mexico City, a bus ride to Tehuacan southward down the arid central valley, and then, following an overnight stop, another bus to the mountain town of Zoquitlan, gateway to the Sierra. From there, the camp was only 19 km away, on a knoll above the village of Oztopaulco, but this required a drive along a very rough stony track. Somehow two local taxis managed to negotiate it, taking well over two hours. Once there, we found a large central tarpaulin shelter, equipped with benches and a long dining table, and a well-stocked and organised kitchen, all put together from local fallen wood. The view was of forested mountains up to 3,000 high. A waterfall emanating from a spring was the shower, a few minutes walk away.

And there were the Belgians, as warm and supremely competent as Boon made them out to be all those years ago. As well as the Great Rescue veterans, there were younger GSAB cavers, two keen Mexicans, a Frenchman, and Nazanin Yaghmaei, a very impressive Iranian woman who has taken part in recent expeditions to Ghar Jojar, her country?s deepest cave at almost ? 1100 metres and still going.

The victuals, as one might expect, were excellent, with weekly shopping trips accomplished via the expedition?s two 4x4s augmented with fresh tortillas, eggs and other produce delivered daily by villagers. So too was the craic: there is nothing quite like Mexican rum and ?Big Cola? after a long day underground.

A drive further up the track brought us to the start of the path to the La Muneca entrance, a tough uphill slog made tougher on the day of our first trip by relentless morning heat. That day, our main enemy was dehydration: 5 litres of water between four of us, it was to become clear, simply wasn?t enough.

The GSAB cavers had already rigged the cave, and in the process had discovered a new descending passage that had not been pushed to a conclusion by the time we left Mexico. A big entrance hung with creepers led to a scree slope, at the bottom of which we got changed. No need for fleece or Powerstretch here: the cave?s comfortable temperature of 19C meant oversuits, Ron Hills and T-shirts were sufficient.

The first, very short pitch led off down from the changing area. Beyond lay a giant version of Eastwater Cavern on Mendip: a steeply descending passage that follows the dip of the thinly-bedded limestone, interrupted by about 15 drops that are either proper pitches or climbs needing a rope. None is bigger than 20m, and many of them are not really vertical, but smooth slabs. In places, the passage was impressively large: at least 10m wide and perhaps 40m high. There were several knee-deep pools, and one short crawl, a ?blowing hole? formed by a fallen boulder.

Towards the end of the stream passage, the passage required us to stoop. But then, unexpectedly, I detected a strange reverberation: a hint of something bigger up ahead. Abruptly we emerged into the echoing vastness of the main chamber. Scurions on full power barely made a dent.

In the course of two trips to the chamber we began to get to know it. Forming a flat crescent along the bottom is an area of flat mud. At the far end is a big passage and a climb leading to a pitch: the cave ends in a choke not far beyond. Three waterspouts pour down from rents in the faraway roof. Above the flat crescent is a scree and boulder pile of enormous dimensions. On the first day, while Pete and Tim scanned, I climbed up to its summit. Some of the GSAB cavers were working on a photo about halfway down. From where I stood they seemed impossibly distant, their lights remote twinkles. Verbal communication with them was impossible, my words swallowed up by the echo.

It seemed a long way uphill to get out from the bottom, especially with a dessicated throat. On the second trip, two days after the first, a cooler walk made the whole venture easier.

All too soon it was time to leave the GSAB camp and return to civilisation, via a convivial dinner in Mexico City with Ramon Espinasa, founder of the Sociedad Mexicana de Exploraciones Subterraneas, his caving wife Ruthie, and their daughter, Sophia, who at 14 has the family passion for caving and is already proficient at SRT.

Tim and Andy thought it likely the La Muneca cavern will make the world top ten. I will be awaiting the result of the data processing to be done by Roo Walters ? who, sadly, was unable to join us ? with eager anticipation.

Last week, Andy Eavis, Tim Allen, Pete Ward and I shared a forest camp in the nearby Sierra Negra with some of the heroes of this story and went caving with them. Etienne Degrave, the doctor who tended Huber underground for days, Richard Grebeude and Jean-Claude ?Jack? London may be rather older now, but they have lost none of their enthusiasm for underground adventure. Thanks to the many books and articles about it and the hard-charging personality of its leading light, Bill Stone, the Huautla project is more famous, and a little deeper. But Degrave, Grebeude and their friends from the Group Speleo Alpin Belge (GSAB) have quietly been knocking off extraordinary achievements 30km away from Huautla for many years. Their finds include one cave more than 1,300 metres deep, a total of six deeper than 1,000 meters and several systems more than 20 km long ? all managed on just a tiny fraction of the corporate sponsorship amassed by Stone?s group and its attendant media hoopla.

We were in Mexico for a specific purpose: as part of the Eavis ? Allen giant cavern laser scanning project, we wanted to make a 3D scan of the main chamber of La Muneca, discovered by GSAB at a depth of -450 m in 1999 and not visited since.

It took a while to reach basecamp: a flight to Mexico City, a bus ride to Tehuacan southward down the arid central valley, and then, following an overnight stop, another bus to the mountain town of Zoquitlan, gateway to the Sierra. From there, the camp was only 19 km away, on a knoll above the village of Oztopaulco, but this required a drive along a very rough stony track. Somehow two local taxis managed to negotiate it, taking well over two hours. Once there, we found a large central tarpaulin shelter, equipped with benches and a long dining table, and a well-stocked and organised kitchen, all put together from local fallen wood. The view was of forested mountains up to 3,000 high. A waterfall emanating from a spring was the shower, a few minutes walk away.

And there were the Belgians, as warm and supremely competent as Boon made them out to be all those years ago. As well as the Great Rescue veterans, there were younger GSAB cavers, two keen Mexicans, a Frenchman, and Nazanin Yaghmaei, a very impressive Iranian woman who has taken part in recent expeditions to Ghar Jojar, her country?s deepest cave at almost ? 1100 metres and still going.

The victuals, as one might expect, were excellent, with weekly shopping trips accomplished via the expedition?s two 4x4s augmented with fresh tortillas, eggs and other produce delivered daily by villagers. So too was the craic: there is nothing quite like Mexican rum and ?Big Cola? after a long day underground.

A drive further up the track brought us to the start of the path to the La Muneca entrance, a tough uphill slog made tougher on the day of our first trip by relentless morning heat. That day, our main enemy was dehydration: 5 litres of water between four of us, it was to become clear, simply wasn?t enough.

The GSAB cavers had already rigged the cave, and in the process had discovered a new descending passage that had not been pushed to a conclusion by the time we left Mexico. A big entrance hung with creepers led to a scree slope, at the bottom of which we got changed. No need for fleece or Powerstretch here: the cave?s comfortable temperature of 19C meant oversuits, Ron Hills and T-shirts were sufficient.

The first, very short pitch led off down from the changing area. Beyond lay a giant version of Eastwater Cavern on Mendip: a steeply descending passage that follows the dip of the thinly-bedded limestone, interrupted by about 15 drops that are either proper pitches or climbs needing a rope. None is bigger than 20m, and many of them are not really vertical, but smooth slabs. In places, the passage was impressively large: at least 10m wide and perhaps 40m high. There were several knee-deep pools, and one short crawl, a ?blowing hole? formed by a fallen boulder.

Towards the end of the stream passage, the passage required us to stoop. But then, unexpectedly, I detected a strange reverberation: a hint of something bigger up ahead. Abruptly we emerged into the echoing vastness of the main chamber. Scurions on full power barely made a dent.

In the course of two trips to the chamber we began to get to know it. Forming a flat crescent along the bottom is an area of flat mud. At the far end is a big passage and a climb leading to a pitch: the cave ends in a choke not far beyond. Three waterspouts pour down from rents in the faraway roof. Above the flat crescent is a scree and boulder pile of enormous dimensions. On the first day, while Pete and Tim scanned, I climbed up to its summit. Some of the GSAB cavers were working on a photo about halfway down. From where I stood they seemed impossibly distant, their lights remote twinkles. Verbal communication with them was impossible, my words swallowed up by the echo.

It seemed a long way uphill to get out from the bottom, especially with a dessicated throat. On the second trip, two days after the first, a cooler walk made the whole venture easier.

All too soon it was time to leave the GSAB camp and return to civilisation, via a convivial dinner in Mexico City with Ramon Espinasa, founder of the Sociedad Mexicana de Exploraciones Subterraneas, his caving wife Ruthie, and their daughter, Sophia, who at 14 has the family passion for caving and is already proficient at SRT.

Tim and Andy thought it likely the La Muneca cavern will make the world top ten. I will be awaiting the result of the data processing to be done by Roo Walters ? who, sadly, was unable to join us ? with eager anticipation.