christine

Active member

So, I thought I'd test out this new fangled forum and post my blog here on last year's Croatia exped before we head out and do it all again....

Note: The blog is designed for the non caving, non diving public...not seasoned hard core cavers and divers, please bear that in mind when reading.

I'll trickle out the subsequent parts as time and wifi allows. Enjoy!

Part 1: A Tall Order

As the covid-19 saga rolled on into 2021, the likelihood of me being able to get to Croatia with a team to continue pushing the cave Izvor Licanke, looked gloomy.

As June approached, the travel restriction hokey-cokey continued and getting even the most enthusiastic divers to commit was proving impossible.

Travel through France was a no go and with a heavy heart, yet again I had to cancel the expedition.

Preparations had been stop start - how on earth do you plan an expedition when you don’t know who can come, when or even if it will take place and how you will ultimately get there.

Nothing was open, nothing was really working and, admitting defeat, I took a chance on August.

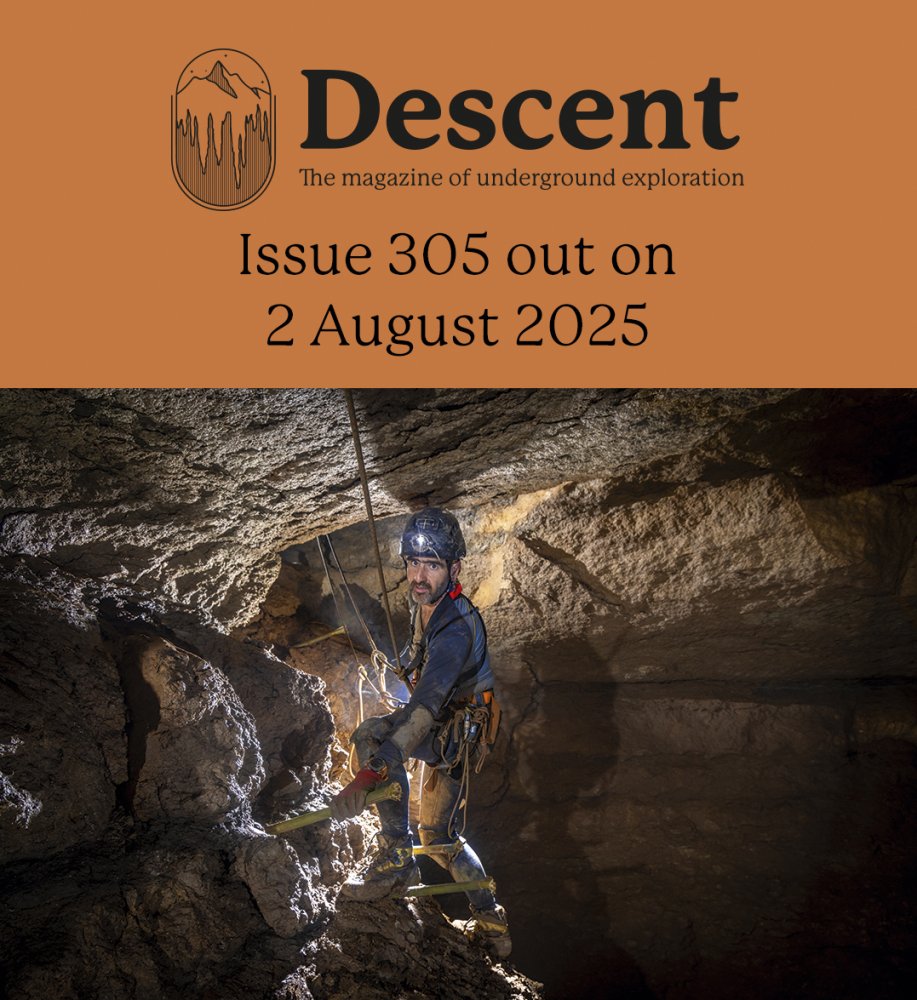

Image: Mark Burkey

Figuring that holidays abroad and getting people moving would be good for somebody’s economy, I took the first of many risks, that partly by luck and partly by judgement, paid off.

For some reason August was rammed for most people so it was with a small team of 5 that we headed out to Croatia, with a tall order ahead of us.

The 2019 expedition had yielded a further 2 sumps beyond the deep sump 2 and the dive line ended some hundred or so metres into sump 4.

We had no idea if sump 4 would surface or plummet deeper. This is both the beauty and frustration of cave exploration - no human has ever been there; it cannot be photographed from space or planned by flying over it or studying it as you can with mountains. Even the world’s deepest ocean trenches have now been mapped.

Caves remain the last frontiers on Earth that cannot be discovered unless you go there in person. Most of the easy pickings have long gone.

We got lucky with Licanke in that access problems for the local cavers and cave divers globally had been lost for 20 years, but we managed with the help of locals, to gain legal access Licanke.

Thus, the end of the line laid by the French prolific cave explorer Frank Vasseur, was ready for the taking and with his permission (always ask, never just take) we began exploring the cave.

Since 2015 my team have now extended this cave by a further 1,229 metres, bringing the total length of the cave system to 1623 metres.

What we lacked in numbers in 2021 we made up for in talent. We are always fortunate to have a National Geographic and globally acclaimed underground photographer, Mark Burkey, on our team, He was taught to cave dive by my own fair hand and has let rip ever since, photographing beyond sumps all over the place in some really quite hard-to-reach places.

Louise McMahon was new to the team and relatively new to cave diving, Highly intelligent and a fast learner, she brought various skills with her but most importantly, is a computer whizz and she offered to re-survey the cave system as far as sump 2 and produce a proper survey of the whole known cave.

Fred Nunn was a last-minute acquisition. I had taken him caving a few times (with WetWellies...all the jokes about grooming my new sherpas came true...) and he took it all in his stride. He had thousands of dives under his belt, all of them in the sea, but it was not a difficult task to up-skill him in the cave diving skills he needed to cross the first short and shallow sump and he passed his course with flying colours.

Fred is often described as ‘Heath Robinson’ - a real problem solver. We hadn’t long invited him when he was already making lead flashing for the dry tubes and weighting systems of all sorts to tidy up our attempts and sinking unwieldy camera boxes and dry tubes.

The two push divers were myself and Rich as our chosen third partner was unable to get out of Mexico due to covid.

C'est la vie.We knew it would be tough - and it was.

Fred helping survey. Image: Mark Burkey

With thanks to The Ghar Parau Foundation and the Mount Everest Foundation.

With thanks to The Ghar Parau Foundation and the Mount Everest Foundation.

Note: The blog is designed for the non caving, non diving public...not seasoned hard core cavers and divers, please bear that in mind when reading.

I'll trickle out the subsequent parts as time and wifi allows. Enjoy!

Part 1: A Tall Order

As the covid-19 saga rolled on into 2021, the likelihood of me being able to get to Croatia with a team to continue pushing the cave Izvor Licanke, looked gloomy.

As June approached, the travel restriction hokey-cokey continued and getting even the most enthusiastic divers to commit was proving impossible.

Travel through France was a no go and with a heavy heart, yet again I had to cancel the expedition.

Preparations had been stop start - how on earth do you plan an expedition when you don’t know who can come, when or even if it will take place and how you will ultimately get there.

Nothing was open, nothing was really working and, admitting defeat, I took a chance on August.

Image: Mark Burkey

Figuring that holidays abroad and getting people moving would be good for somebody’s economy, I took the first of many risks, that partly by luck and partly by judgement, paid off.

For some reason August was rammed for most people so it was with a small team of 5 that we headed out to Croatia, with a tall order ahead of us.

The 2019 expedition had yielded a further 2 sumps beyond the deep sump 2 and the dive line ended some hundred or so metres into sump 4.

We had no idea if sump 4 would surface or plummet deeper. This is both the beauty and frustration of cave exploration - no human has ever been there; it cannot be photographed from space or planned by flying over it or studying it as you can with mountains. Even the world’s deepest ocean trenches have now been mapped.

Caves remain the last frontiers on Earth that cannot be discovered unless you go there in person. Most of the easy pickings have long gone.

We got lucky with Licanke in that access problems for the local cavers and cave divers globally had been lost for 20 years, but we managed with the help of locals, to gain legal access Licanke.

Thus, the end of the line laid by the French prolific cave explorer Frank Vasseur, was ready for the taking and with his permission (always ask, never just take) we began exploring the cave.

Since 2015 my team have now extended this cave by a further 1,229 metres, bringing the total length of the cave system to 1623 metres.

What we lacked in numbers in 2021 we made up for in talent. We are always fortunate to have a National Geographic and globally acclaimed underground photographer, Mark Burkey, on our team, He was taught to cave dive by my own fair hand and has let rip ever since, photographing beyond sumps all over the place in some really quite hard-to-reach places.

Louise McMahon was new to the team and relatively new to cave diving, Highly intelligent and a fast learner, she brought various skills with her but most importantly, is a computer whizz and she offered to re-survey the cave system as far as sump 2 and produce a proper survey of the whole known cave.

Fred Nunn was a last-minute acquisition. I had taken him caving a few times (with WetWellies...all the jokes about grooming my new sherpas came true...) and he took it all in his stride. He had thousands of dives under his belt, all of them in the sea, but it was not a difficult task to up-skill him in the cave diving skills he needed to cross the first short and shallow sump and he passed his course with flying colours.

Fred is often described as ‘Heath Robinson’ - a real problem solver. We hadn’t long invited him when he was already making lead flashing for the dry tubes and weighting systems of all sorts to tidy up our attempts and sinking unwieldy camera boxes and dry tubes.

The two push divers were myself and Rich as our chosen third partner was unable to get out of Mexico due to covid.

C'est la vie.We knew it would be tough - and it was.

Fred helping survey. Image: Mark Burkey